Oliver Wendell Holmes, the nineteenth-century doctor and poet, once said that “The books we read should be chosen with great care, that they may be, as an Egyptian king wrote over his library, ‘The medicines of the soul.’” REMEDIA has collected thoughts from writers and academics working in the medical humanities about the texts beyond their discipline which have influenced their ideas and research. The recommendations below may well be the perfect tonic for your summer vacation.

from Thomas W. Laqueur, Helen Fawcett Distinguished Professor, UC Berkeley.

Twenty years ago my friend, the literary scholar Paul Alpers, now dead, sent me a poem by William Empson called “Ignorance of Death.” The last stanza reads:

Twenty years ago my friend, the literary scholar Paul Alpers, now dead, sent me a poem by William Empson called “Ignorance of Death.” The last stanza reads:

Otherwise I feel very blank upon this topic,

And think that though important,

and proper for anyone to bring up,

It is one that most people should be prepared to be blank upon.

The poet’s call for epistemological modesty came as a welcome relief from a sense that I should have views on this topic if I was to teach students about death and dying or write a book about the dead in history. Perhaps even more than love, death fills the human plenum, like enveloping ether. “There is this civilizing love of death.” “It is the trigger of the literary man’s biggest gun.” I could be content to think about a more limited –but still very big question– of why we care for our corpses.

from Peter D. Kramer, Writer and Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University.

Lately, I’ve been on a Javier Marías binge. I had been introduced to his work when on book tour in Madrid and returned to it when I ran out of translated Knausgård. Both indulge in over-close, overlong description of objects and settings—a European tradition I trace to the prose poems of Francis Ponge—but Marías applies the same method to relationships, including ones incidental to the main action. He will have a character eavesdrop on a lovers’ quarrel and then speculate endlessly about motivations and future outcomes. The books’ plots, generally lurid, serve mostly to move the technique from experimental to mainstream. An unexplained murder or suicide sets the stage for what verges on parody of stream-of-consciousness writing or (natch) psychotherapy. I find this material addictive. I suppose it relates to my work with patients. However extreme I am in my encouragement for us to re-plow exhausted fields, I cannot outdo Marías. More, it energizes my writing. I, too, tend to worry small themes. It’s good to encounter a master who shows that mine is not the extreme case—and that the extreme can be done masterfully.

Lately, I’ve been on a Javier Marías binge. I had been introduced to his work when on book tour in Madrid and returned to it when I ran out of translated Knausgård. Both indulge in over-close, overlong description of objects and settings—a European tradition I trace to the prose poems of Francis Ponge—but Marías applies the same method to relationships, including ones incidental to the main action. He will have a character eavesdrop on a lovers’ quarrel and then speculate endlessly about motivations and future outcomes. The books’ plots, generally lurid, serve mostly to move the technique from experimental to mainstream. An unexplained murder or suicide sets the stage for what verges on parody of stream-of-consciousness writing or (natch) psychotherapy. I find this material addictive. I suppose it relates to my work with patients. However extreme I am in my encouragement for us to re-plow exhausted fields, I cannot outdo Marías. More, it energizes my writing. I, too, tend to worry small themes. It’s good to encounter a master who shows that mine is not the extreme case—and that the extreme can be done masterfully.

The rich and revealing correspondence between Abigail and John Adams was a major inspiration behind my writing Revolutionary Medicine: The Founding Father and Mothers in Sickness and in Health. Although it is challenging for even historians to understand to what degree early American were surrounded daily with sickness and death, their vivid letters provide an intimate window into the reality of illness, epidemics, health and medicine in the 18th century. While John was attending the Continental Congress, Abigail remained at home in Massachusetts with her children and had to cope on her own with the ravages of terrible smallpox, scarlet fever, and dysentery epidemics. In July 1777, she gave birth to a stillborn baby girl while John was still in Philadelphia. The letter John wrote her was one of the most poignant I have ever come across. After remarking that “Providence has preserved to me a Life [Abigail’s] that is dearer to me than all other Blessings in the World,” he went on to observe sadly “ Is it not unaccountable, that one should feel so strong an Affection for an Infant, that one has never seen, or shall see?”

The rich and revealing correspondence between Abigail and John Adams was a major inspiration behind my writing Revolutionary Medicine: The Founding Father and Mothers in Sickness and in Health. Although it is challenging for even historians to understand to what degree early American were surrounded daily with sickness and death, their vivid letters provide an intimate window into the reality of illness, epidemics, health and medicine in the 18th century. While John was attending the Continental Congress, Abigail remained at home in Massachusetts with her children and had to cope on her own with the ravages of terrible smallpox, scarlet fever, and dysentery epidemics. In July 1777, she gave birth to a stillborn baby girl while John was still in Philadelphia. The letter John wrote her was one of the most poignant I have ever come across. After remarking that “Providence has preserved to me a Life [Abigail’s] that is dearer to me than all other Blessings in the World,” he went on to observe sadly “ Is it not unaccountable, that one should feel so strong an Affection for an Infant, that one has never seen, or shall see?”

A Fortunate Man (1967) is an intimate study — text by Berger, photographs by Mohr — of the working life of an English country doctor, John Sassall. It’s a book about attention, tact, and the hard work of sustaining sympathy and imagination. All of this applies as readily to Berger and Mohr as to Sassall. The physician is also an embedded intellectual, laboring to understand his patients’ existential fears and ambitions as well as their symptoms. (An exemplary instance: during a house call to an old couple, the wife turns out on examination to be a man. Sassall remains diplomatically silent.) I discovered A Fortunate Man when I was writing about memories of family illness in my first book, In the Dark Room. But I return to it now as much to be reminded what an alert and humane essay can achieve, as for what the book has to say about bodies and minds.

A Fortunate Man (1967) is an intimate study — text by Berger, photographs by Mohr — of the working life of an English country doctor, John Sassall. It’s a book about attention, tact, and the hard work of sustaining sympathy and imagination. All of this applies as readily to Berger and Mohr as to Sassall. The physician is also an embedded intellectual, laboring to understand his patients’ existential fears and ambitions as well as their symptoms. (An exemplary instance: during a house call to an old couple, the wife turns out on examination to be a man. Sassall remains diplomatically silent.) I discovered A Fortunate Man when I was writing about memories of family illness in my first book, In the Dark Room. But I return to it now as much to be reminded what an alert and humane essay can achieve, as for what the book has to say about bodies and minds.

I’m not sure how old I was when I first read Alice in Wonderland & Through The Looking Glass but I won’t have been much over age seven. Wonderland and Looking Glass are worlds that were alien to me — in their Victorianism and phantasmagoric dreamscapes — yet also instantly recognizable: they felt a bit like ‘home’, in the oddest way. In his narratives, Charles Dodgson pits this bright little girl against all sorts of contrary, self-absorbed individuals, who pick arguments with her and baffle her with their insistent crazy logic. Forty years later I came across uncanny echoes of many of these ‘Alice’ conversations when I immersed myself in the case histories of the Victorian governmental inspectorate, the Commissioners in Lunacy. And who was one of the most important members of that body? Dodgson’s beloved uncle, WS Lutwidge (1802-1871). There’s no paper trail to prove it, but I am convinced that details ‘leaked’ conversationally from uncle to nephew and then into the Alice books.

I’m not sure how old I was when I first read Alice in Wonderland & Through The Looking Glass but I won’t have been much over age seven. Wonderland and Looking Glass are worlds that were alien to me — in their Victorianism and phantasmagoric dreamscapes — yet also instantly recognizable: they felt a bit like ‘home’, in the oddest way. In his narratives, Charles Dodgson pits this bright little girl against all sorts of contrary, self-absorbed individuals, who pick arguments with her and baffle her with their insistent crazy logic. Forty years later I came across uncanny echoes of many of these ‘Alice’ conversations when I immersed myself in the case histories of the Victorian governmental inspectorate, the Commissioners in Lunacy. And who was one of the most important members of that body? Dodgson’s beloved uncle, WS Lutwidge (1802-1871). There’s no paper trail to prove it, but I am convinced that details ‘leaked’ conversationally from uncle to nephew and then into the Alice books.

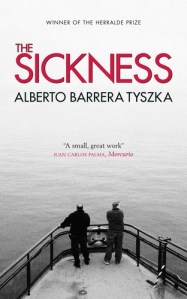

I came across the award-winning Venezuelan writer Alberto José Barrera Tyszka’s The Sickness (La Enfermedad, 2006) two years ago while working on my book on global world literature and health. The novel centers on a physician (Dr. Miranda) whose father is diagnosed with terminal cancer. Particularly intriguing is that despite Dr. Miranda’s extensive experience dealing with the terminally ill, his insistence throughout the years on a “transparent relationship between physician and patient” (whether or not the patient actually desires such a relationship), and his father’s own pleas for openness, Dr. Miranda finds it nearly impossible to speak with the elder Miranda about his fatal condition. Like many illness narratives, including Philip Roth’s Patrimony (which I teach together with The Sickness), Tyszka’s novel highlights the difficulties communicating illness. What makes The Sickness particularly poignant is its depiction of transparency as possible only in the relative absence of feeling.

I came across the award-winning Venezuelan writer Alberto José Barrera Tyszka’s The Sickness (La Enfermedad, 2006) two years ago while working on my book on global world literature and health. The novel centers on a physician (Dr. Miranda) whose father is diagnosed with terminal cancer. Particularly intriguing is that despite Dr. Miranda’s extensive experience dealing with the terminally ill, his insistence throughout the years on a “transparent relationship between physician and patient” (whether or not the patient actually desires such a relationship), and his father’s own pleas for openness, Dr. Miranda finds it nearly impossible to speak with the elder Miranda about his fatal condition. Like many illness narratives, including Philip Roth’s Patrimony (which I teach together with The Sickness), Tyszka’s novel highlights the difficulties communicating illness. What makes The Sickness particularly poignant is its depiction of transparency as possible only in the relative absence of feeling.

As a young man Hunter Thompson once typed out the entire text of The Great Gatsby, just to get the feel of writing such extraordinary sentences. I’m tempted to do the same with Thompson himself. Thompson did not write great books, but he wrote a lot of breathtakingly venomous paragraphs, and the best of them concerned our 37th president. Take this passage from Thompson’s obituary for Nixon: “If the right people had been in charge of Nixon’s funeral, his casket would have been launched into one of those open-sewage canals that empty into the ocean just south of Los Angeles. He was a swine of a man and a jabbering dupe of a president. Nixon was so crooked that he needed servants to help him screw his pants on every morning.” No American writer has ever made moralizing seem as fun and subversive as Thompson, and few moralists are rewarded with enemies as twisted as Nixon. In addition to the Nixon obituary, “He Was a Crook,” I’d recommend “Presenting: The Richard Nixon Doll (Overhauled 1968 Model)” which is reprinted in The Great Shark Hunt, and if you’re willing to try book-length Thompson, try Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72.

As a young man Hunter Thompson once typed out the entire text of The Great Gatsby, just to get the feel of writing such extraordinary sentences. I’m tempted to do the same with Thompson himself. Thompson did not write great books, but he wrote a lot of breathtakingly venomous paragraphs, and the best of them concerned our 37th president. Take this passage from Thompson’s obituary for Nixon: “If the right people had been in charge of Nixon’s funeral, his casket would have been launched into one of those open-sewage canals that empty into the ocean just south of Los Angeles. He was a swine of a man and a jabbering dupe of a president. Nixon was so crooked that he needed servants to help him screw his pants on every morning.” No American writer has ever made moralizing seem as fun and subversive as Thompson, and few moralists are rewarded with enemies as twisted as Nixon. In addition to the Nixon obituary, “He Was a Crook,” I’d recommend “Presenting: The Richard Nixon Doll (Overhauled 1968 Model)” which is reprinted in The Great Shark Hunt, and if you’re willing to try book-length Thompson, try Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72.

from Richard Barnett, Wellcome Trust Engagement Fellow emeritus and author of The Sick Rose.

Writing about my love for Geoffrey Hill is like writing about the Atlantic. Beyond a few basic facts, anything one says will sound inadequate, diminishing, unworthy. Hill is our finest poet of memory, and across six decades of writing he has come back again and again to the fundamental questions of how to bear witness, how to speak honestly, how to bear the weight of flesh. He is also, in the words of Colin Burrow, ‘a profoundly cussed writer’, wielding a grouchy and abrasive wit. Now in his eighties, Hill bears a startling resemblance to Bengt Ekerot’s Death in The Seventh Seal, and in late-period sequences such as Speech! Speech! he comes on like an Old Testament prophet miraculously endowed with wifi and a Bodleian Library card. He can gnash and grumble with crackling density (‘AMOR. MAN IN A COMA, MA’AM. NEMO. AMEN.’), and yet he remains deeply underrated as a poet of the body, of sensuality and delicacy:

Writing about my love for Geoffrey Hill is like writing about the Atlantic. Beyond a few basic facts, anything one says will sound inadequate, diminishing, unworthy. Hill is our finest poet of memory, and across six decades of writing he has come back again and again to the fundamental questions of how to bear witness, how to speak honestly, how to bear the weight of flesh. He is also, in the words of Colin Burrow, ‘a profoundly cussed writer’, wielding a grouchy and abrasive wit. Now in his eighties, Hill bears a startling resemblance to Bengt Ekerot’s Death in The Seventh Seal, and in late-period sequences such as Speech! Speech! he comes on like an Old Testament prophet miraculously endowed with wifi and a Bodleian Library card. He can gnash and grumble with crackling density (‘AMOR. MAN IN A COMA, MA’AM. NEMO. AMEN.’), and yet he remains deeply underrated as a poet of the body, of sensuality and delicacy:

How is it tuned, how can it be un-

tuned, with lithium, this harp of nerves? Fare well

my daimon, inconstant

measures, mood- and mind-stress, heart’s rhythm

suspensive; earth-stalled | the wings of suspension.

–

Reblogged this on C19 Mad Men and commented:

Recommended summer reading for those interested in the history of medicine.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on DailyHistory.org and commented:

Remedia had has asked eight medical historians which books “influenced their ideas and research” but had absolutely nothing to do with their academic discipline. Not surprisingly, the list has an interesting mix of poetry, fiction and non-fiction. It even includes a work of young adult (YA) fiction that Ruth Graham recently railed against at Slate. As I made clear in an earlier post, thank goodness we just ignore Graham’s advice.

LikeLike